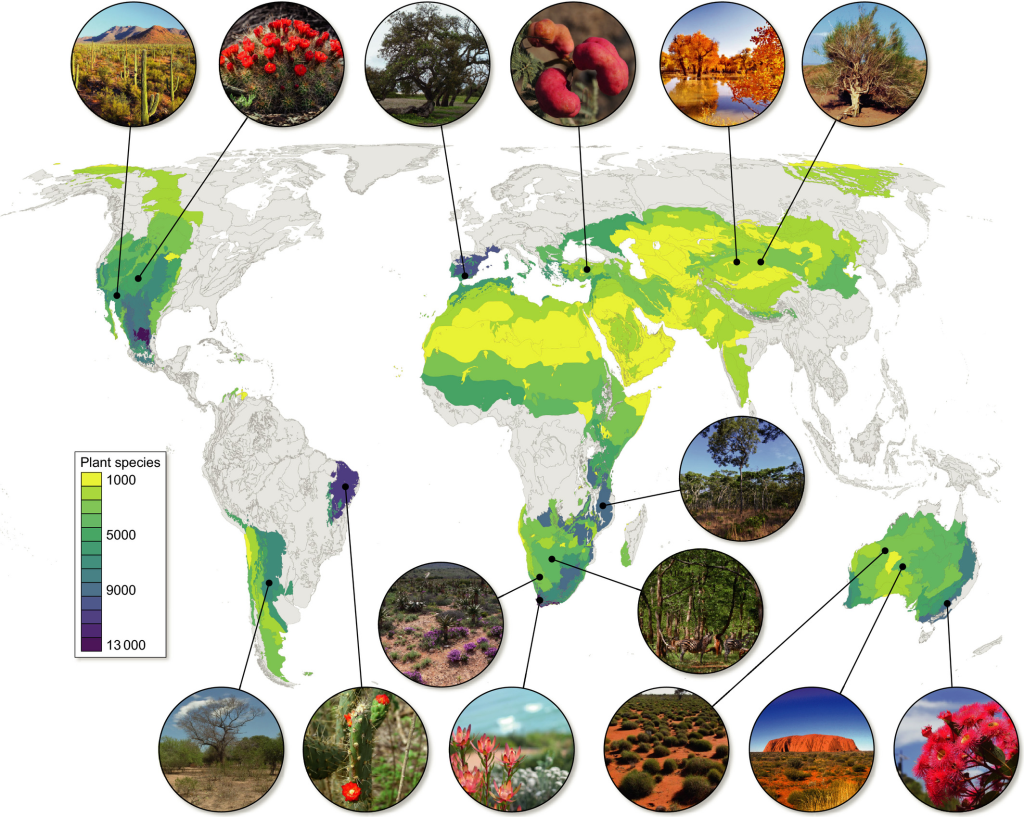

Drylands don’t often make headlines. They’re not lush like rainforests or dramatic like melting glaciers. But behind their cracked soils lies one of the most surprising biological stories. Drylands cover over 40% of the planet’s land surface, across six continents, and quietly support more than two billion people. Despite limited rainfall and harsh environmental stressors, drylands are biodiversity-rich. They contain 35% of global plant diversity hotspots and support remarkably high levels of endemism—species found nowhere else. (Maestre et al. 2021)

These landscapes are seen as fragile, degraded, or empty. Yet when scientists explore the details of dryland vegetation, they find an impressive range of survival strategies. And the drier it gets, the more creative plants seem to become. Recently three scientists from INRAE, the CNRS, and the King Abdullah University referred to a phenomenon known as Plant Loneliness Syndrome as part of their large-scale study involving 120 researchers from 27 countries. (Gross, Maestre, Bagousse-Pinguet et al. 2024)

Fig. 1—Plant species richness of the world’s dryland ecoregions and examples of vegetation types that can be found in drylands worldwide. (Source: Maestere et al. 2021)

Plant Loneliness Syndrome: The secret life of arid flora

In extremely dry and heavily grazed ecosystems, a curious pattern emerges. As the aridity index climbs past 0.7, the usual rules of ecology start to fall apart. The relationship between plant traits such as height, leaf size and nutrient content begins to unravel. Instead of converging on a few optimal strategies, plants diverge wildly. They, in a sense, become loners. This phenomenon, referred to by authors as “Plant Loneliness Syndrome,” captures how dryland plants break traditional ecological assumptions. Where functional trait diversity increases by 88%, even as species richness declines. (Gross, Maestre, Liancourt et al. 2024)

But how did this diversity evolve in the first place? (Maestre et al. 2021, Berdugo et al. 2021)

Two eco-evolutionary mechanisms, among others, can help explain it:

- In-situ niche evolution: Many dryland plant lineages adapted over millions of years to local conditions, diversifying during arid epochs like the Miocene and Pliocene. Families such as Cactaceae and Aizoaceae radiated within drylands, becoming masters of their environments.

- Dispersal to track shifting niches: Other species adapted by moving—following climate shifts to find new suitable habitats. Yet, this doesn’t always succeed. When plants can’t keep pace, they face eco-evolutionary lag—falling out of sync with the environment, which can reduce their ecological effectiveness.

Together, several such mechanisms reveal why drylands are not uniform—they’re mosaics of evolutionary strategy, shaped by both stability and movement.

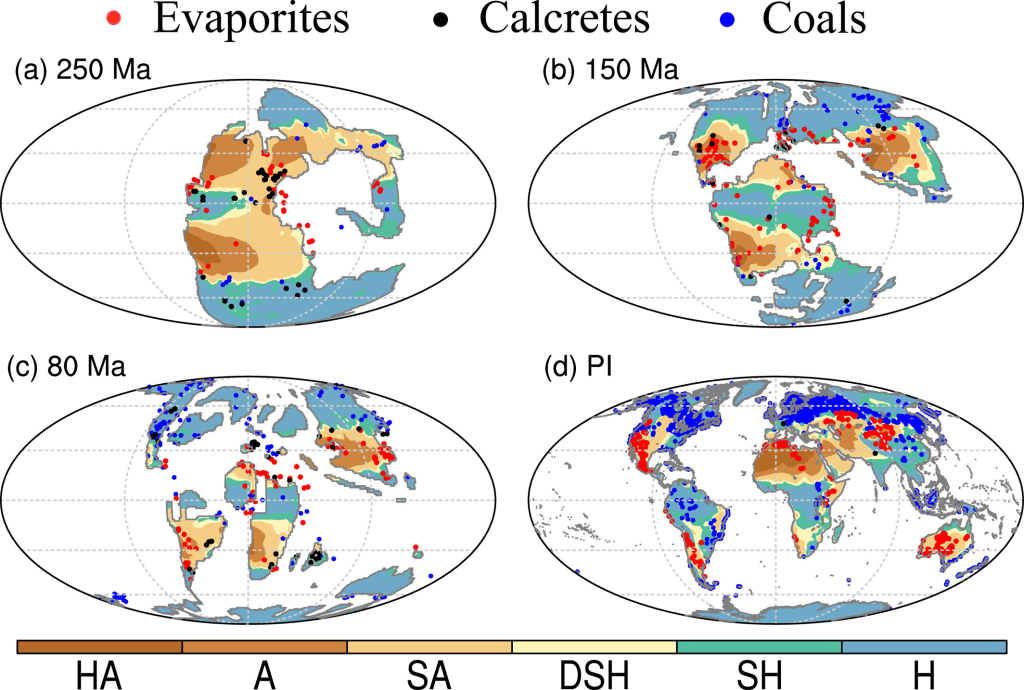

Where did the first drylands form?

To understand today’s drylands, we must go back to the supercontinent Pangea, around 250 million years ago. During that time, vast inland regions were dry—over 56% of the land surface qualified as arid. They drifted and broke apart; drylands contracted and then expanded again. By the Cretaceous period, they made up only 32% of Earth’s surface. Today, they’ve regrown to about 40%, but their geography and structure have dramatically changed. (Li et al. 2025)

Some modern drylands carry the imprint of this deep history:

- The Namib Desert houses Welwitschia mirabilis, a plant with no close relatives for over 100 million years.

- Australia’s arid center hosts acacias and saltbushes that evolved with continental isolation.

- The Loess Plateau and Central Asia’s deserts reflect ancient monsoonal drying and glacial cycles.

Each of these regions tells a story—not just of climate, but of how life carved out niches in seemingly unlivable places.

Fig. 2—Evolution of terrestrial aridity and drylands since Pangea (Source: Li et al. 2025)

Dry and humid regions for (a) 250 Ma, (b) 150 Ma, (c) 80 Ma, and (d) Pre-Industrial. Color shading denotes hyper-arid (HA; AI < 0.05), arid (A; 0.05 ≤ AI < 0.2), semi-arid (SA; 0.2 ≤ AI < 0.5), dry sub-humid (DSH; 0.5 ≤ AI < 0.65), semi-humid (SH; 0.65 ≤ AI < 1.0), and humid (H; 1.0 ≤ AI). Red, black, and blue dots denote records of evaporites, calcretes, and coals (paleoclimatic proxies).

How drylands are strangely full of life?

With climate change accelerating, drylands are expected to expand, especially semi-arid zones moving into currently temperate regions. But how these systems respond depends not only on rainfall or temperature but on how quickly plants can adapt. In drylands, fewer species doesn’t mean less diversity—it means more unique adaptations to survive:

- Water-use strategies (deep roots, water storage tissues, fast life cycles)

- Leaf and stem traits (tiny, waxy leaves vs. nutrient-packed flushes)

- Growth timing and persistence (long-lived shrubs vs. opportunistic herbs)

Drylands are repositories of ecological genius—places where plants have persisted, adapted, and diversified through some of Earth’s most volatile climates. They may offer clues for future resilience, and this is where understanding deep-time perspectives becomes vital!

I am Mudit, and my work in AGRI-DRY focuses mainly on deciphering how the Holocene climate shaped the origin and spread of dryland agriculture in Africa and the Mediterranean and quantifying how food secure we might be in the near and long-term future. I am also broadly interested in topics of how paleoclimatic and paleoecological processes shaped and continue to shape the present and future of our planet.

Know more about Mudit and his work here…

References: